Insights

These high level insights have been formed from our work with people living with dementia, and help shape our approach to new ideas, products and services.

Facilitating productive interactions

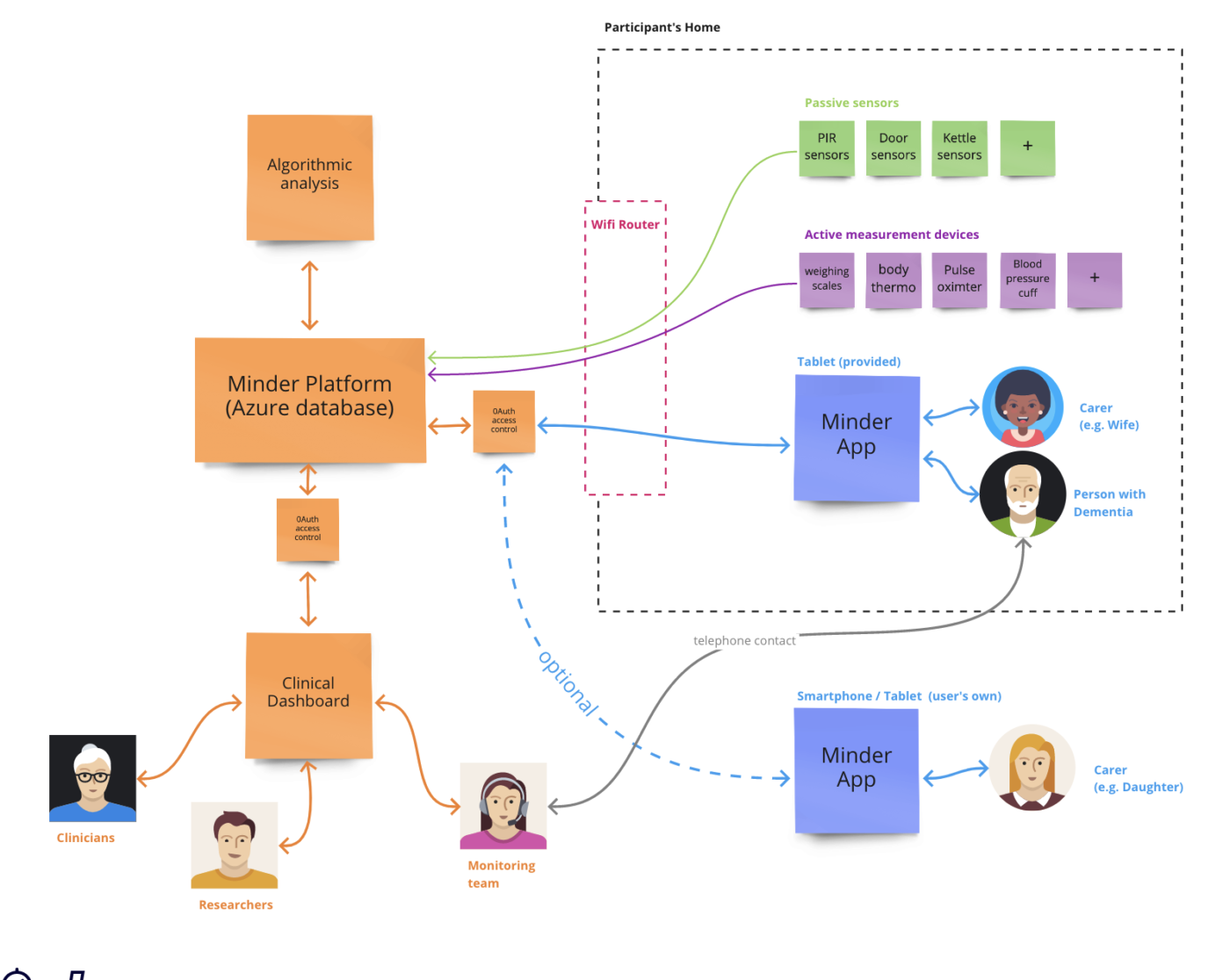

The Minder system employs a small monitoring team that responds to data coming into the homes, and contacts the carers of participants to solve problems, suggest clinical interventions, and find out what is causing the data characteristics. This may involve frequent phone-calls. Some participants get great benefit from the regular conversations with a familiar voice, and appreciate knowing that someone is keeping an eye on them. Other carers find them time consuming, and frustrating, entirely depending on their living, working, family arrangements. The design of the Minder dashboard and Minder App is fundamental in facilitating personalised interactions between researchers and participants, helping the monitoring team get to know the participants, avoid unwanted calls, and provide communication formats to suit the individual.

Design as a filter for competing interests

A common issue for our participants is the extent to which being part of the study is itself a help or hindrance to the daily routine of caring for someone with dementia. Participation offers the benefit of clinical monitoring, which helps avoid hospitalisation through early treatment of infection and other benefits. While we aim for ‘passive monitoring’ as an ideal, research requires a lot of validation through active measurements (pulse oximetry, temperature, blood pressure), and surveys. We have a lot of competing research interests looking for the attention of relatively few participants. As designers, part of our role is to protect the participants’ experience, and make sure it is accessible and rewarding. Our Human Centred Design process has become a filter for the patient experience, making sure interventions meet a high level of usability and acceptability. As part of this effort we created the Minder brand – to make accessible the huge array of organisational labels involved in this centre, and to provide consistency and clarity throughout.

Thinking beyond the stereotypes

We have seen first hand how individual’s dementia affects them in different ways, and of course how it changes over time. People often associate dementia with very passive days lived in care-homes, but that is only the case as dementia enters the advanced stage. Technology has a lot to play in the early and middle stages of dementia, where it can be used to enable and preserve independence, dignity and control for individuals. We are aiming to help people throughout the dementia progression, from getting a diagnosis, to supporting them to maintain their independence and chosen lifestyle for as long as possible. Instead of thinking about an individual’s abilities and inabilities, it can be helpful to think about roles (e.g. remembering medications or preparing food) within a person’s care, acknowledging that roles may pass from the person with dementia to carers. As such, you can design products that can be used by either the person with dementia, or their carers, or both. For example the daily questions in the Minder Companion App.

Provide opportunities for deeper involvement

While visiting participants who were taking regular measurements (weight, blood pressure, temperature etc) using internet enabled devices to send the data to researchers, we found that many participants were also noting down their readings with pen and paper for their own reference. They typically wanted to be able to share information with GPs during consultations, or just keep track of how they are doing. This inspired us to create the Minder companion app to give participants proper access to their data. We extended this idea to include an observation diary, to allow carers and people with dementia to record relevant observations for both the researchers, and their own use. It has also been apparent in the Minder Watch project, that providing accessible data feedback to users with dementia is important to maintain their interest and engagement with a device. We don’t expect every user to engage to the same level, but we create the opportunity for varying levels of engagement.

Neuro-diversity is more than a one-way street

Designing for dementia is to design for a hugely varying range of abilities, aspirations and needs. Cognitive abilities range from genius to minimal, and with it comes the huge variety of lives lived; professions, interests, culture, politics, all making up the identity of the individual. Different forms of dementia have differing effects on individuals, and the skills and interests they retain. This matters when introducing new technologies. A good example is the Minder Check-in using Alexa. For some people with dementia, Alexa is an alien concept, a disembodied voice and a source of confusion. For others, Alexa is a lifeline – an intuitive interface using the most natural input of voice, that can provide entertainment, reminders and help, and even safety in the home. We can’t and shouldn’t hope to suit everyone in this demographic with any single intervention.