Minder Check-in

Collaborators:

Dr Ravi Vaidyanathan, Reader in Biomechatronics

Dr Maitreyee Wairagkar, Research Associate

Maria Raposo de Lima, Research postgraduate

Matthew Harrison, Designer

Pip Batey, Designer

and Minder Champions / research participants.

What is the need?

The robotics stream within the UK DRI Care Research & Technology Centre, based in Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College, aims to explore the potential of voice agents, with and without accompanying avatars and mechanical robotics, as accessible interfaces for people affected by dementia to engage with digital systems.

Voice has an exciting potential for many people with dementia. It is arguably the most intuitive and flexible ‘input/output system’ we have as humans, and the ability to interact verbally remains in many people with dementia until the advanced stages.

Project stage

What are the aims and objectives of the project?

People with dementia represent a vast range of cognitive abilities, and different types of dementia have different characteristics in terms of the type of cognition retained and lost over time. Cultural variables are another important consideration, for example, individuals’ experience of technology in their lives before dementia can potentially have an impact on how appropriate voice interfaces may be. Therefore, it was important to acknowledge that voice interfaces are unlikely to be universally appropriate for people with dementia. However for some people, voice interfaces could represent a real and valuable opportunity to engage and include people as dementia progresses.

The aims of this project focussed initially on exploring the potential of voice interfaces via off-the-shelf platforms such as Amazon’s Alexa and Google home. The objective of this ongoing project is to understand the potential for these technologies to enable and assist in many aspects of care for someone with dementia. Furthermore this project aimed to investigate whether the use of ‘voice’ could help with obtaining daily well-being information from the participants to assist with the broader study.

How is the project approached?

Designers worked with engineers from the robotics team from the start, facilitating workshops with people affected with dementia to provide early input into how voice interfaces might be useful for people living with dementia and carers. When COVID19 restricted the ability to work with users in person, online video conferencing was used to ask users to help us explore potential ‘voice’ experiences.

The team decided the first voice based intervention would be centred around asking the participants three daily well-being questions, which would be used to provide valuable context to the wider study. This formed the basis of the Alexa Skill (equivalent to an App on a smartphone). However Alexa devices with accounts managed centrally are also being provided to allow researchers to also investigate the wider use and potential voice interfaces. The team are keen to explore if mood and other variables can be detected from the audio signals from interactions with Alexa.

What role does Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) play in this project?

In our initial home visits to understand the broader requirements of participants, we observed the use of Alexa and Google devices in the home, and asked participants how they used them. This enabled the early discovery of valuable insights described below that could inform the product development strategy.

Later workshops with carers and people with dementia were held to test and demonstrate early prototypes on Alexa and Google home devices, to understand how it might be applicable to the dementia context.

As the prototypes developed online sessions were held with Minder Champions to focus on the details of the interactions in the emerging Alexa skill.

What were the key insights to emerge?

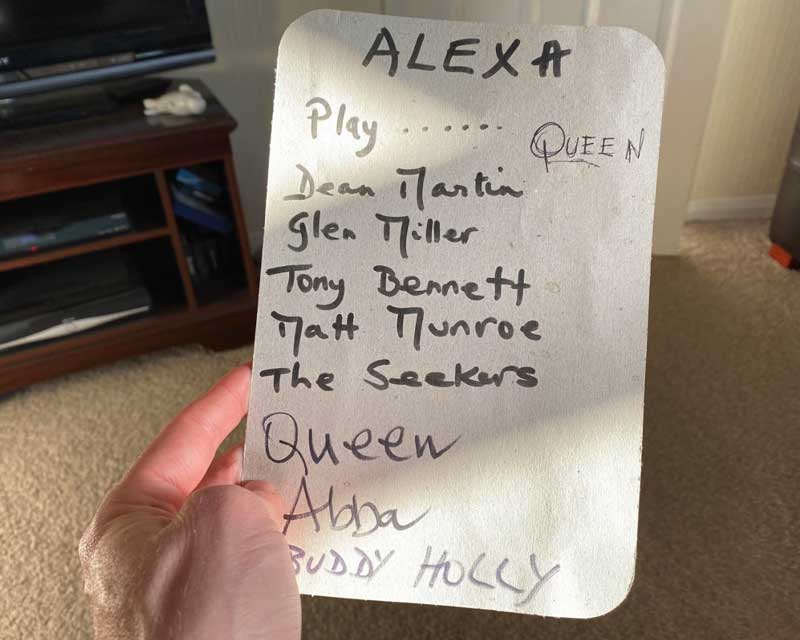

From the initial background research and house visits at the start of Helix’s involvement in the centre, it was clear that the Alexa in particular played an important role in the daily lives of some people with dementia. We found several examples where Alexa was used to provide entertainment and music for the person with dementia, in a way that gave them autonomy and control. “Prompt cards” were often used to remind the user how to initiate the Alexa, and make suggestions or what to ask of Alexa, for example favourite music choices.

We heard of other specific applications, including an example of a person with dementia who would repeatedly ask his wife what time of day it was, often testing her patience . Diverting this question to the Alexa, with its limitless patience, meant that tension in the household was greatly reduced.

Some carers spoke of concerns that people with dementia may be confused by ‘disembodied voices’ and we heard anecdotes of people searching in cupboards for the person behind the voices. This applies specifically to functions where the device is perhaps initiating the conversation (for example, providing a medication reminder) rather than responding to a user’s question.

There is also an interesting question around whether or not a familiar voice (e.g. that of a relative) is helpful or detrimental in providing the prompts from the device. Something we are keen to explore.

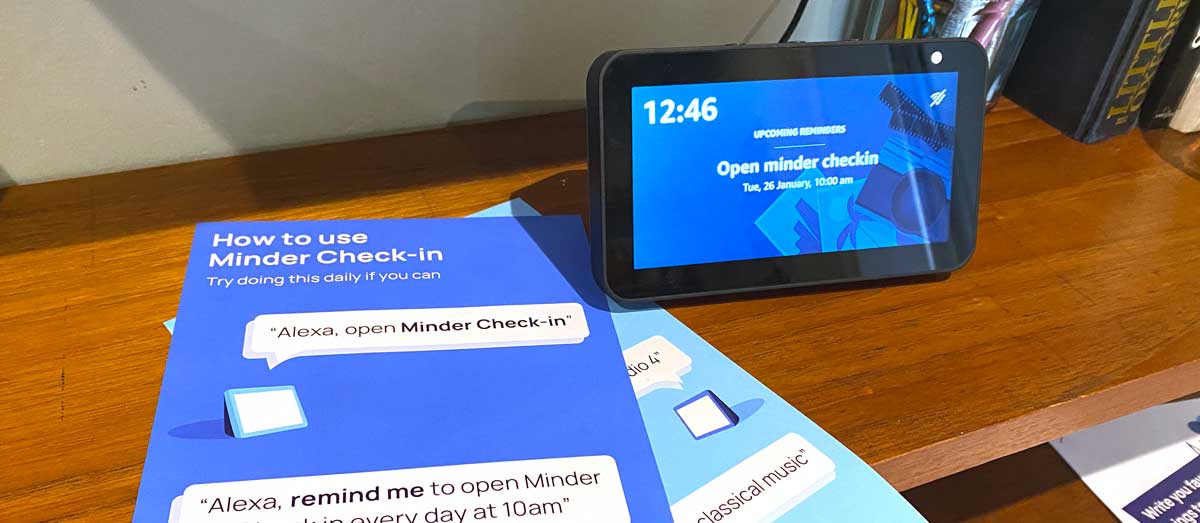

One other aspect to be explored is the value of having a screen on the device to support interactions. For example the smart-hub versions of the Alexa devices feature a screen that can show example responses to questions posed to users. Will reading ‘multiple choice’ answers simply prompt users to respond according to default answers, and miss the real opportunity of voice agents in being able to support conversational answers that reflect more honest and personal responses? Will the combination of listening and reading promote or dilute confusion on the part of a user with mild to moderate cognitive loss?

An important aspect to emerge from the Alexa work was to consider very carefully the on boarding experience. We needed to be very clear in explaining what the purpose of the Alexa device was, what information would be recorded and available to whom, and how to set it up on their home wifi. This need is currently heightened as we are not able to visit homes to install the devices during COVID19 restrictions, To respond to this, we created a few videos and written instructions to guide people through the onboarding process.

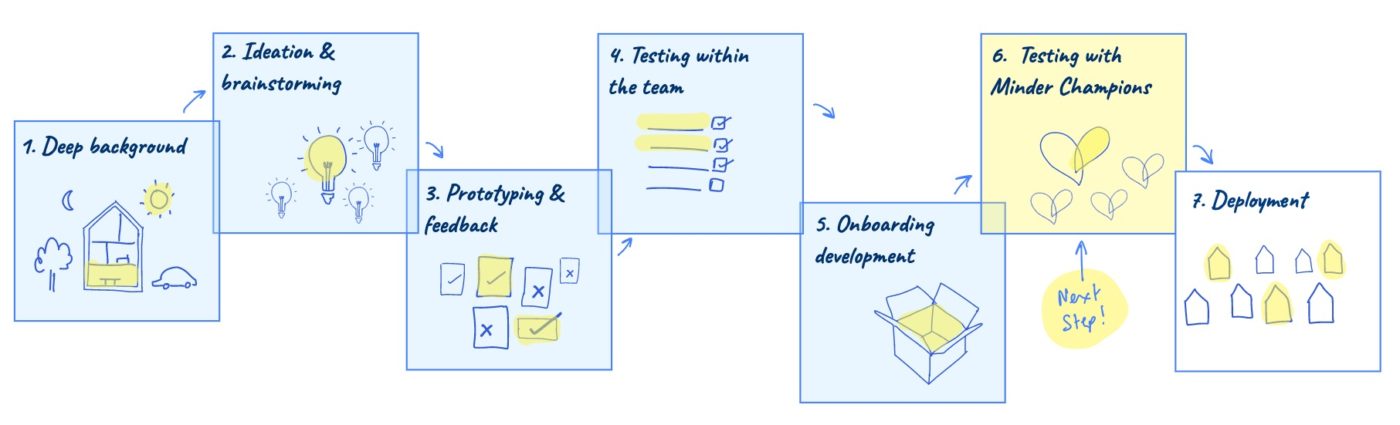

The Alexa project also served as a great way to hone our design to delivery process, ensuring that we ironed out as many issues as possible before expecting people affected by dementia to use the device themselves. We tested the skill within the design team, and with other colleagues first, focusing particularly on the onboarding experience, reserving the ‘valuable resource’ of study participants for a more developed solution. We describe this process here.

Next steps

At the time of writing, we are due to send out the first 4 devices to Minder Champions as our first ‘real-life’ users. They will provide regular feedback on the onboarding process and continued used of the device for the first few months, before we iterate on that feedback and deliver it to a wider cohort within the study.